My babci (grandmother), Róża, was only seventeen when she boarded the train to Antwerp—alone— near Kolno, in northeast Poland. It was December 1911, three years shy of the turmoil of World War I.

Stars sparkled in the moonlight on the coarse crust of the deep frozen snow and young Róża drew her cheap coat closer against the bitter cold. She stamped her feet to warm them.

When the train left the station that night, its whistle merged with the whistling wind and the howling of wolves in the forest, lifting with it the spirits of passengers bound for the Christmas holidays in Western Europe. Others on board, like Róża, may have shed a few tears for Mama and Ojciec left behind.

Odwaga

noun– on możliwość zrobić coś, co przeraża jedno.

I was eighteen, sitting silently in the back seat of my father’s Ford, when I began my own journey from our rural farm to Amherst, Massachusetts, bound for freshman orientation at the University of Massachusetts. I had never been to UMASS. The trip to Amherst— 49.7 miles—might as well have been across the ocean. Amherst would be my Antwerp.

Courage

noun– the ability to do something that frightens one.

I didn’t know a soul there, except for my orientation roommate. A classmate from my high school, she was, frankly, very sexy for a high school student and her voluptuous breasts made me feel even more like the boyish freak that I thought I was.

When we went to the Student Union Bookstore to buy t-shirts to show off our college student status to our peers back home, we held up the shirts to our bodies, trying to judge the sizes.

I knew right away that I was a t-shirt size Small.

Rifling through the stack of athletic grey shirts, my roommate asked, “What size do you think I should buy?”

Without hesitation, I said, “Extra-Large.”

“University of Massachusetts” would surely be distorted by the peaks and valleys of those breasts if she chose a smaller size.

We left the Student Union with our purchases and changed into our new t-shirts back at the dorm.

Mine fit perfectly, not too tight, not too loose, its hem reaching just a few inches below my waist.

Hers, unfortunately, fit like a nightgown.

I was shocked. At that moment I realized that our bodies were not all that dissimilar. Sure, she was sexier and she still had bigger breasts, but I suddenly grasped that my self-image was significantly distorted.

It was a testament to her good nature that she didn’t berate me for my poor judgment, but I’ll never forget my embarrassment.

We enjoyed the introduction to college life during that week. Not good enough to want to be freshman roommates, but good enough.

When it came time to leave home for the school year two weeks later, I once again sat silently in the back of my father’s Ford, this time with my mother in the front passenger seat and my youngest brother, a kindergartner, sitting in the back with me and my record turntable.

It didn’t take too long to unpack the car when we got to Amherst. One red Samsonite suitcase, one red Samsonite train case, my stereo and my milk crate of records. My family drove away without much comment. Certainly there were no hugs and kisses.

I lay back on my bed and listened to the quiet.

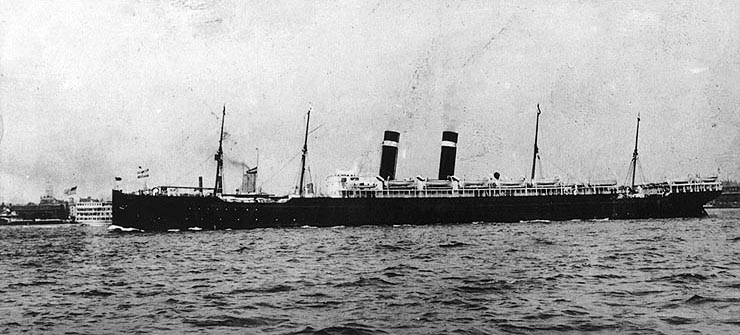

At Antwerp, Róża boarded the gangplank of the passenger ship Finland with all of the other young people in steerage class. Was she also fleeing a less than happy home life?

She watched her trunk being stacked on the baggage wagon and hauled on board. Everything she owned was in that trunk. Her clothing, her Sunday church shoes, her rosary, a knitted shawl and a basket woven of native willow. Being peasant Polish, she couldn’t afford a stylish feathered hat like those she had seen en route. More likely, she wore a babushka, like the ones she wore almost every day for the rest of her life.

Steerage class on the Finland proved to be its own education, and Róża also was the victim of distorted information.

One day over cups of tea in her kitchen on the farm, Babci told me that she first saw people with black skin during that trans-Atlantic crossing. Someone told her they were devils. She laughed self-consciously when she said this. It was the slightly embarrassed character of that laugh that communicated to me—a ten-year-old who had only seen black people on television—that she might have actually believed it. She didn’t know better. Not any better than the 18-year-old college student who truly thought that her orientation roommate had a figure of outlandish proportions.

Oftentimes, I opened Babci’s trunk in the attic on the farm when I was sent up to fetch onions from the braids that hung from the rafters. The trunk stood near a window under the peak of the roof. It was empty inside, and its pale paper lining had flaked away in parts. I often opened and shut its lid multiple times, clasping and unclasping the draw-bolts, and running my fingers along its wooden slats while daydreaming of Róża, curled up in a bunk, trying to stay warm with her mediocre steerage-issued blanket, as the Finland rose and fell on the high seas.

The devils sometimes infiltrated the dreams that she had of a new life in America as she slept in her bunk in the Finland.

A couple years later, the devil in her world became the man whom she would meet in a small town in Connecticut and marry, beginning a life within the farmhouse where the trunk sits in the attic, empty of her dreams.

My red Samsonite cases traveled with me for quite a few years, and they too eventually crossed the Atlantic. When their linings began to smell slightly of mildew and they had served their purpose, I donated them to the Salvation Army.

Babci’s willow basket sits in my kitchen today where it contains my last memories of my grandmother and the times we spent together. I think that she’d be surprised to learn that not long after college, I became quite a proficient basket weaver.

At eighteen, I was navigating my own troubled waters. Having grown up in a cold and hostile household where animosity always seemed to be simmering beneath the surface, I had not yet learned how to communicate properly with others. I’d always been a loner.

At sea on the Finland, Róża was alone too, preferring to keep to herself as Christmas came and went.

Three days later, when Róża processed through the Great Hall on Ellis Island on December 28, I suspect that she received the greatest Christmas gift of her life. For her, Ellis Island was the “island of hope.” The Ellis Island Immigration Museum describes how others, who were not permitted entry, found Ellis Island to be an “island of tears” as they were put on ships and returned to their countries of origin.

What if Babci had never arrived in the America? What if her spirit had not harbored the desire to surpass her humble beginnings? What if she had placidly continued to live the peasant life somewhere in Eastern Europe, killing and plucking chickens on a tree stump in her barnyard?

What if, supposing that I still had been born—but with different genealogy—I had never arrived at UMASS? What if I had stayed at home and, as my father had proposed, had gotten that job operating a keypunch machine at the factory? Or, barring that, apprenticed to become a bank teller, in spite of my absolute incompetence with numbers?